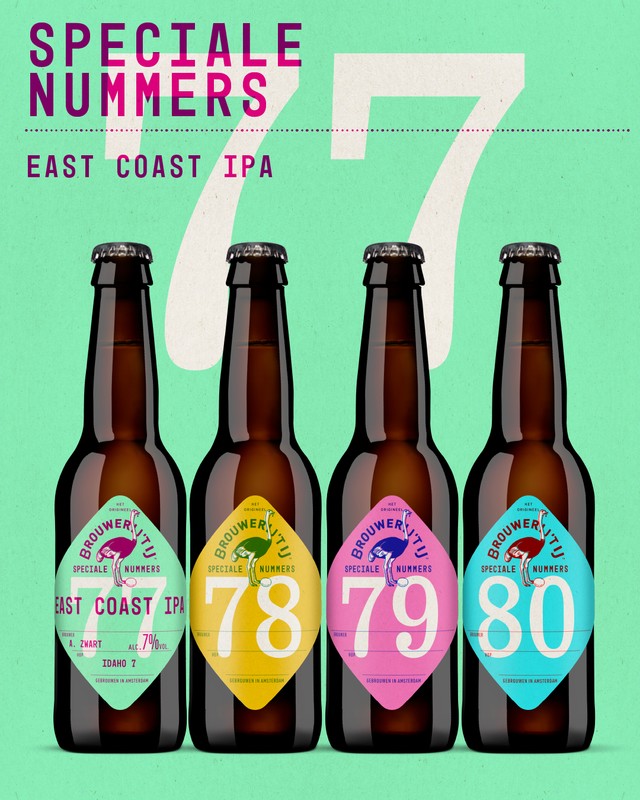

The first in a new series: number 77

We tried to count how many beers we brewed since we kicked off with Zatte Tripel. in 1985. Don’t hold us to it, but we counted 76 beers. Not all of those beers made it into our fixed range, but they all taught us something about brewing. Our brewers are constantly working with new ingredients and techniques and to keep on showing you what they have to offer, we introduce something new: special numbers.

A range of beers in which our brewers are given the space to put their personal stamp on that typical profile of ‘t IJ with distinctive recipes.

We asked Allard Zwart to think about the first beer in this series. It’s called number 77, because we just keep counting. Allard likes to push the boundaries of what is possible with malt, hops and yeast. He previously brewed a delicious New England IPA with so-called cryo hops for the De Molen tasting room.

Those cryo varieties contain about twice as many oils as other types and are specially freeze-dried to separate those oils from the less usable parts. All hops contain oils, which give beers a pleasant floral aroma. With a bit of luck, they can also give a beer a velvety fullness. A serious complication is that brewing is a process that many of those oils do not survive. Allard brewed with a blend of those special hops. A major advantage of this so-called Cryo-Pop blend is that it contains oils that withstand cooking and fermentation well above average. That New England IPA already tasted like more because of those fine oils. The special songs are ideally suited to further explore what else can be done with them.

For our number 77, Allard wanted to further investigate the effect of the mentioned oils. “I reached out to the folks at Yakimi Chief, who produce cryo-hops and recommended that I check out Idaho 7.” That is a hop that provides a soft tropical fruitiness, think mango. Nice to use a lot. “Crazy amounts of hops went into this beer,” said Allard. “I think I used five times more than usual.” Normally we only add this type of aromatic hops during lagering, the process in which the beer slowly ‘tastes’ after fermentation. For number 77, part of the hops went into the tank before storage. “Because there is still a lot of yeast in suspension and the beer has not yet been cooled, you promote biotransformation. The yeast then bonds with the oils and can convert some of the hop oils into more desirable oils.” That is not entirely without risk. “It also released quite a bit of carbon dioxide,” Allard grins. “It really squirted out of the tank.”

All those hops and chemical chaos resulted in a surprisingly balanced beer. It’s a lot like the beers they brew so well on the East Coast of the United States: IPA’s that are less bitter than the almost aggressively hoppy varieties of the American West Coast. East Coast IPA’s have a full hoppy aroma without their fruitiness overshadowing the soft maltiness. “I wasn’t going to brew a typical East Coast IPA, but if you have to put a label on it, it just ticks off a few important things.” What exactly does that mean? “It’s nice and full, both in terms of malt and hops, but it doesn’t go wrong,” Allard concludes with satisfaction.

In his take on this style you can taste a nice soft fruitiness and slightly resinous touch of pine. You can recognize the bottle of this beer by a large special number and the name of the brewer on the label: A. Zwart.